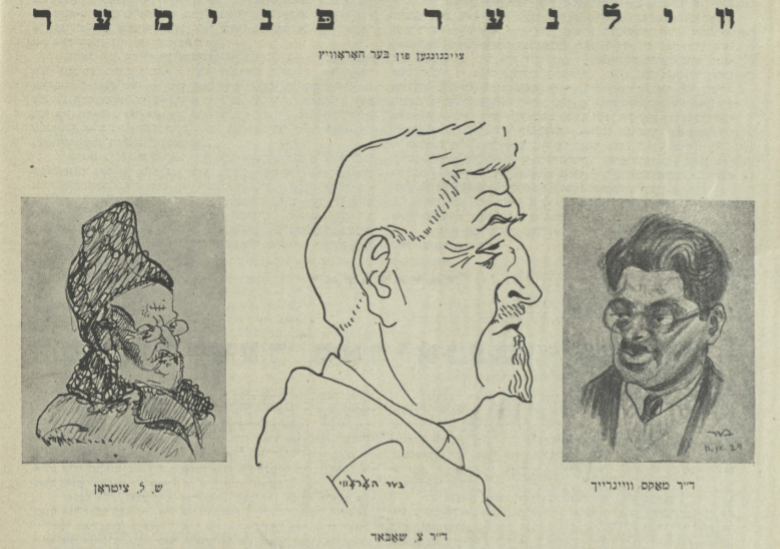

My Lexicon - Ber Horovits (Horowitz, Horowic)

- Corbin Allardice

- Feb 18, 2021

- 3 min read

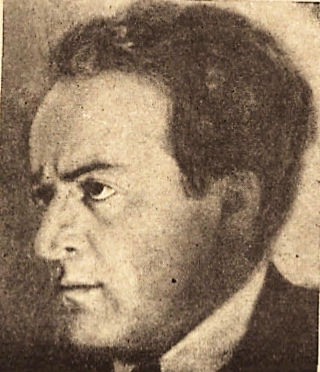

Ber Horovits

Born 1895 in Maydan (Majdan), a village in Eastern Galicia. Soldier in WWI; Trips to Vienna, Berlin, Paris. Lived in Vilne (Vilnius) for a time, later--until 1939--in Stanisławów (Ivano-Frankvisk). Tragic news about him in 1939. However he lived and worked. More tragic news in 1943.

Ber Horovits has more craft than most Yiddish poets. He sings loudly. His poetry is tumultuous. It’s like that folk song “How does the tsar sleep at night?--A hundreds soldiers stand screaming ‘SHH, SHH, SHH” (viazoy shloft der keyzer baynakht?--Shteyen hundert soldatn un shrayen sha, sha, sha)...Horovits’ first book of poems was called fun mayn heym in di berg (From my Home in the Mountains.) He would never again sing (ibergezungen) the poems in that little book. He would reach the truest pitch he could and never again try to recapture that magic.

He also wrote fables (mayselekh) about the Bal Shem Tov. He invented them himself and he illustrated them himself and he would lead us [readers] somewhere deep in the mountains...his language is a kind of Yiddish-Ukranian pidgin (khotse-goyish--palovine yidish)...

He developed an exceptionally powerful talent for illustration, he was an excellent portraitist, a fact which, to a certain extent, confused him: “What am I?” But it’s hardly novel for a poet to be, at the same time, a painter--and vice-versa.

But I’ve been going on as a critic does about a friend, one I have known since 1908. Again: One-thousand nine-hundred and eight. We were classmates at the Hebrew school in Stanisławów in Galicia.

We had a teacher, a Hebrew writer named Shammai Khalatnikov, who hated tardiness and disruptions. Horovits was thirteen at the time and wore a little student’s uniform with three silver stripes on the collar. He was a third year student (fun dritn klas) at a gymnasium (high school) at the time and I was a student at a trade school. In the evening, we attended the Hebrew school. Horovits was always late and always used the same trick so that the teacher wouldn’t notice. He jumped over all the seats to his own. Over heads, inkwells, notebooks, books--and he was big, so he all but hit the rafters in the course of his leap. Well the class ran amok, a tempest in a teapot, a revolution. The sole person to sit quietly in their seat in the midst of the ambient maelstrom, to sit quietly in the corner by the wall was Horovits...naturally. He never trampled his head under feet, never spilled his inkwell, never kicked his books. The inquisition, which promptly began, led nowhere, and the person who had caused the great unrest was the person who now most vocally wondered as to who could possibly have leapt over the class like a demon; that is to say, he was Horovits.

Later, I encountered him in Vienna. We had both become soldiers defending the Austria empire...Horovits was already a medical student and a sanitation corporal. I can imagine the great commotion with which Horovits would keep the angel of death at bay. After the war, we were close to the journal kritik (Criticism) in Vienna. It was then that Horovits first debuted with a book of poems. And we often met in Warsaw, uncountably often.

Horovits was the only son in his family, his father died young, and he had a complicated family life and could rarely sit still, rarely write. That alienated him, to some degree, from the trajectory of our literature. He was eternally a sparrowhawk who would swoop down from the heavens, cause a stir, and return on high.

Horovits’ poem afn veg tsum ekzertsir-plats (On the Way to the Parade Ground) is one of the most sincere, truly pacifistic poems we have. It is rarely noted and rarely recited. For us, quality must swim in a great bowl of quantity. How else could you become famous?

Ber Horovits the painter is a chapter of its own. Perhaps the main chapter. We covered whole walls in the Warsaw Yiddish Writer’s Association with his caricatures of Yiddish writers. In his poetry, he is direct [prost], often raw--in his sketches, he is fine and refined and terribly witty. He educes the deepest expression of the individual he paints. He knows world painting, has written a cycle of poems about world-famous painters, but that is not the field in which he finds his perfection, he hasn’t the patience, he takes the world while leaping over chairs, inkwells, and open books, just as he did in the prime of his youth in Hebrew school. That’s how he is, he cannot be otherwise.

1938

Comments